This blog is on theabsolutesound.com, and I’m an audiophile, so the answer to the title question, at least in my view, is obviously “no”. Or “No!” That’s not the interesting response to the question.

I think one interesting part (there are several IMHO) is a partial explanation for why audiophiles do what they do. Audiophiles spend a lot of time “obsessing”, or we might say “working on” in more neutral language, getting audio systems to sound more like real music (a.k.a. The Absolute Sound). At one level, I think we should say that working hard on something of value seems like an admirable program to follow. You just don’t often hear parents say “I want my kids to be slackers, with no direction in life”.

In addition, some of the critique of audiophiles seems to revolve around their (our) focus on getting better, more accurate sound. That critique seems weird and misguided too, given that a lot of people really like music and a similarly very large number of people seem to think it is admirable for, say, Bill Belichick (head coach of the New England Patriots football team) to spend decades and decades of his life trying to make a football team better than other football teams. Of course, Belichick is handsomely paid for his efforts, but then we don’t say that embezzlers are good people because they get rich but Mother Teresa is despicable because she earned very little in cash.

Then there is the view that spending large sums of money on hi-fi equipment makes no sense because the return on investment is poor. This view, when held by friends, is often similar to the view of friends who “hate Thai food” but upon questioning admit that they haven’t eaten any. A similar view comes from logic like “$100,000 for a stereo?! That’s crazy, I could buy a car for that!” Which, given the minimal functional differences between $100,000 and $50,000 cars, might be understood as “if I’m going to spend money, it has to be to show off to others how rich I am, not to deliver intrinsic value.” Okay, I guess, but not really. And for people who view spending $100,000 on anything as nuts, I must mention your house. Where I live, which is in a mid-priced housing market, an extra 1000 sq. ft. costs about $300,000. And lots of people buy 4000 sq. ft. houses instead of 3000 sq. ft houses. So, who is nuts? It isn’t super obvious, really. We’re back to “people just aren’t that logical”.

Okay, so people aren’t consistent in their value judgements. And they are socially influenced more than logically influenced. So, my view would be that we can safely ignore what friends and The New York Times say about audiophiles.

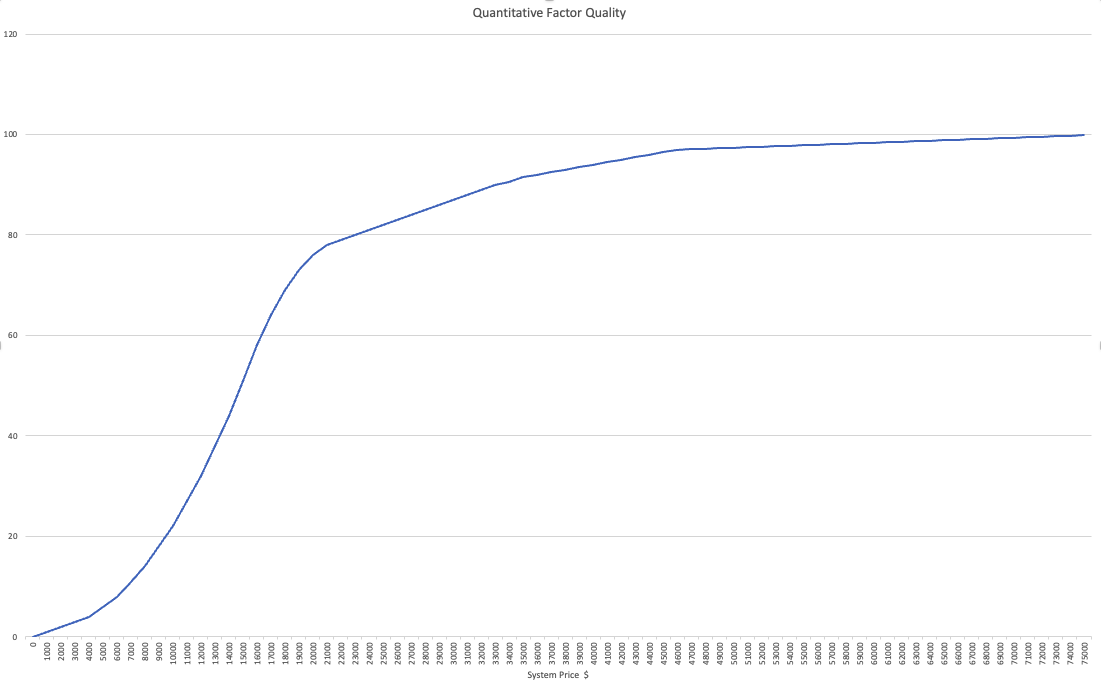

But there is a “killed by friendly fire” element to audiophilia that deserves some added exposition. Robert Harley’s recent Editor’s Letter touched on this, but I want to expand on it. Audiophiles seem confused about the prices of some gear these days. I’ve previously highlighted the uninformed pronouncements of audiophiles who “know” what products cost and “know” that expensive gear is a rip-off. I want to highlight two other elements of misunderstanding. Let me illustrate with this fabricated graph:

I think this illustrates how many people think about the value of audio gear. The chart shows system price on the bottom (X) axis and on the left (Y) axis it shows Quantitative Factor Quality. QFQ is a term I’ve invented for the elements of a hi-fi system than can be readily counted, like number of drivers, size of speaker, size of speaker drivers, amplifier power, MIPS of DSP processing, word length of DAC processing, diameter of cables, number of subwoofers, etc. The graph proposes that you can get about 80% of the maximum QFQ by spending up to around $20,000 and after that QFQ doesn’t go up much. And after about $50,000 system price, it barely rises at all.

Since there is no relationship I know of that linearly relates QFQ to sound quality and realism, the argument that spending on the flat part of the curve is stupid is similar to the argument about investing in expensive cars rather than expensive stereos. I just don’t buy it as relevant to what we should care about as music lovers.

I think a more useful way to understand the audio world is this:

This fabricated graph shows how realism changes with system price. As with the QFQ graph, you gain a lot going from $0 to $20,000 or so. As you progress, you add valuable qualitative elements like lower distortion, wider frequency range, dynamic capability, smoother polar radiation, etc. These are important because they affect the realism and your experience of listening to music, not because anyone in your social circle has any idea of these qualities in the abstract.

But notice a few differences from the QFQ graph. First is that at $20k, we’re only about 40% up the Y axis on the way to high realism, whereas we’re more like 80% up the QFQ axis. I think this means that audiophiles who seek to go beyond this spending level are searching for something real and attainable.

A problem illustrated here is that going above the $20k level means it takes more financial work to gain sound quality or realism. People on a budget might reasonably stop at about this spending level (or lower). But given how wonderful music is, it doesn’t seem insane to keeping pushing if you can. And, there is a certain pleasure and disciplinary benefit and intellectual challenge to moving up the flatter part of the curve. One reason I think some people view work on system refinement on the flat (middle) part of the curve as crazy is that progress isn’t guaranteed. You can spend more and get worse results. You have to then refine you understanding of how systems work to make positive progress. A lot of life is like that.

The other interesting thing about the chart is that the gains per dollar accelerate (or can accelerate) again at very high prices. This isn’t automatic, but it is possible. There is a certain point, in my experience, where a lot of the obvious distortions have been reduced and now each subsequent distortion reduction is more audible and more musically consequential. This helps explain why so many reviewers and dedicated audiophiles and OEMs are so fascinated with the “exotic” end of the spectrum. They’ve heard what can happen and it is beautiful.

Wanting to experience what artists had in mind seems like the opposite of crazy.

The post Philosophical Notes: Are Audiophiles Crazy? appeared first on The Absolute Sound.