-

×

Vinyl Records Cleaner Easy Groove Concentrate

2 × €25.00

Vinyl Records Cleaner Easy Groove Concentrate

2 × €25.00 -

×

Easy Start Vinyl Records Cleaning Kit

1 × €40.00

Easy Start Vinyl Records Cleaning Kit

1 × €40.00 -

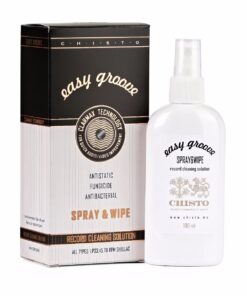

Easy Groove Spray&Wipe vinyl records cleaner

1 × €25.00

Easy Groove Spray&Wipe vinyl records cleaner

1 × €25.00 -

Vinyl Records Cleaner Easy Groove Concentrate

1 × €25.00

Vinyl Records Cleaner Easy Groove Concentrate

1 × €25.00

San Francisco, CA (October 1, 2020)—If audio pros listening to the Working Class Audio podcast take away one thing, Matt Boudreau hopes it’s the lesson of diversification. As every studio hound learns, all it takes to lose your recording is a single point of failure. Running a studio business, he says, works the same way.

“One thing I preach about endlessly on my show is diversification of income and creating income streams, making it so there’s not a single point of failure,” says Boudreau. “This pandemic has really highlighted the strength of that concept.”

“One thing I preach about endlessly on my show is diversification of income and creating income streams, making it so there’s not a single point of failure,” says Boudreau. “This pandemic has really highlighted the strength of that concept.”

As the podcast’s creator, host and producer, Boudreau knows what he’s talking about. When he was a recording studio owner in San Francisco in the 2000s, he had a hard time navigating the Great Recession—and once the financial tension spread from work to his home life, he knew he had to make some changes. He also knew he wasn’t the only one in that situation.

“I didn’t have a strong financial sense about me,” says Boudreau. “I thought, ‘I have to completely rethink this approach. I want to do audio, but I don’t want to fail financially. I’ve got to come up with more of a ‘working class audio’ way of doing things.’” That meant shutting down his studio and rebuilding his career through freelance audio work. And then it meant starting a podcast.

Boudreau established the Working Class Audio podcast to share his experiences, as well as provide a forum for other audio pros to share their stories—how they’re surviving, how they deal with money and how they create work-life balance while continuing to work in audio at the level they want. “Everybody’s story is very different,” he says, “and everybody’s situation is vastly different. Some people have been far more successful. Jacquire King’s story is going to be vastly different from Michael Rosen’s story, or Steve Albini’s.”

After more than 300 episodes, Boudreau still produces the Working Class Audio podcast from the Bay Area home-based mixing and mastering studio where he does much of his work these days. He typically conducts his interviews over Zoom while recording locally to a Sound Devices MixPre-6 through either an AEA KU5A hyper-cardioid ribbon mic or an Audio-Technica BP40 dynamic mic.

One benefit of interviewing studio engineers and producers is not having to worry about getting bad audio from them when he syncs. That wasn’t always the case, though. “The early episodes don’t sound that good, but the later episodes do,” he confesses, noting that those initial segments were recorded over Skype. “It took me a while to figure out, ‘Oh yeah, I could just have them record themselves.’ And it worked. Now the quality of the show is closer to that NPR goal.”

In his transition to freelance work, precision and speed became more important than ever, and Working Class Audio puts those principles into action. Turnaround on an episode is typically one week from recording to publishing. He and editor Anne-Marie Pleau send Pro Tools session files back and forth, running them through iZotope RX to reduce accidental noises and even subtle annoyances like the whoosh of a computer fan.

Once the podcast goes out to the world, what comes back to him are often tales of listeners’ own experiences. The goal, though, is for others to not have to learn the hard way.

“I have learned so much from guests over the years,” he says. “But when listeners send me an email and say, ‘Hey man, I drive a van for a living and I’m getting into a studio situation, and I followed the advice that this guest gave, and this guest gave, and you gave, and I’m really doing well’—that’s when I think, okay, this is serious. This is providing something of value to people.

“As those messages come in, I think my focus is shifting. It’s not so much about what I want to learn, but about what I want others to be able to get out of it.”

Working Class Audio podcast • https://solo.to/wca

Matt Boudreau • www.mattboudreau.com

Easy Start Vinyl Records Cleaning Kit

Easy Start Vinyl Records Cleaning Kit  Easy Groove Spray&Wipe vinyl records cleaner

Easy Groove Spray&Wipe vinyl records cleaner